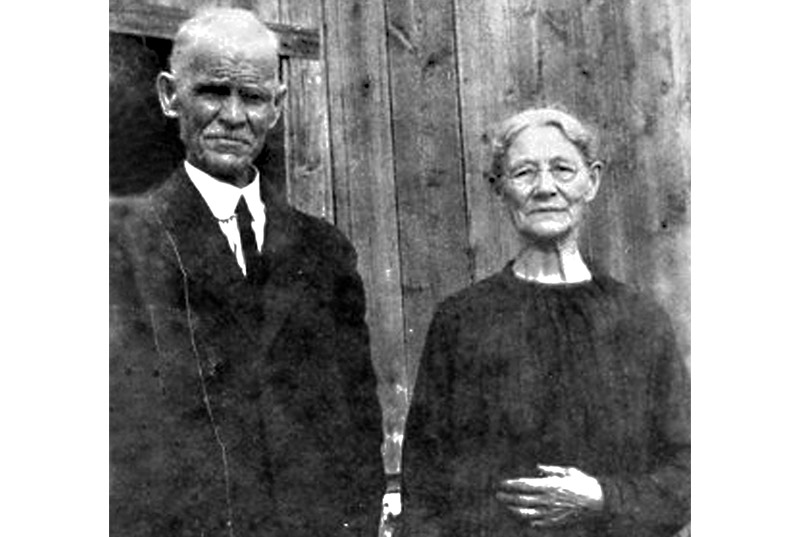

Charles & Susan Macdonell. Courtesy Photo

By M. Eleanor McGrath

AgriNews Contributor

Years ago, an Irish film was made called The Field which told the story of a family struggling to keep the farm and at the very cost of their soul for the salvation of the field.

At the core of the story was the Celtic connection to the land, to the lifeblood of our existence and in turn that of the family’s.

Just recently a guest arrived for a short stay at our Yurt here in Apple Hill, an almost 5-hour drive from their downtown two-bedroom condo in Toronto. For fifteen months, she had been planning the great escape from the Covid lock-down and put us on her route to “reset”. For us, having spent most of our lockdown here at Springfield Farm it was easy to forget how restrictive this experience has been for most Canadians and especially for many living in cities across our country. To hear our guest was to have a reminder that what we have found in Apple Hill, Southeastern Ontario is more than a slice of heaven – it is freedom.

Often when I’m working in our fields, driving the tractor, scratching out rows for seeds, or walking alongside the Beaudette River with the dogs, the soundtrack of “Give me land, lots of land, don’t fence me in” runs its chorus through my head. This might not be prairie flat stretching fields but they certainly are ones that can remind me of drives through the Irish countryside that ring familiar to my Celtic roots.

When we first bought our farm in 2014, it was with a great desire to have a farm for our family of four children with limited farm knowledge (read the summers that my Irish husband spent working on Bresnan’s farm in County Cork!). In fact, buying this farm was fraught with fear, fear of, could we make it as farmers?; could we financially survive?; and would it be something that our children would take on after we’re gone? Some of these questions have been answered, and not in a straight trajectory, but with a lot of tears, struggles and some feelings of elation when what we have sown is actually growing! One piece of advice that was given early on by many of our city friends was we could always sell the property if things didn’t work out – and at the very least sever the house from the land to sell for a profit. Even seven years ago that solution sounded like defeat. To enter the ring of farming is to put your entire body and soul into the battlefield and get dirty and hope for victory. But there’s drought, flooding, financial stress and family concerns that make this more than a struggle – farming is a career.

As we drove our daughter to camp this weekend, we passed the Holland Marsh one of our province’s, possibly our country’s, most rich, iconic and protected soil. As a Torontonian, I have seen this land many times over my 56 years and the beauty of this stretch of topsoil bearing produce is that it always looks the same. There is thankfully in this province a strong respect for agricultural land and its zoning is mandated for protection but sadly as with any system, there are ways to circumnavigate legislation and arguments of progress and economics that put the land and all the habitats, environments and ability to feed nations at risk. Driving up our lane to Springfield Farm it would appear to the untrained eye that the lands are all fallow. But peek over the crest of grasses, you will see the orchard in progress, the sunflowers shining, and rows of tomatoes protected by said grasses. We are in full bloom and there is a long-term focus on our environmental farm oasis as we term our farming. When we walked the 118 acres in spring 2014 tears of fear, awe and wonderment filled my eyes. How after 200 years had this land remained intact except for a small tract moved into the Domtar reforest program? The windbreaks grown up over the impossibly large boulders and dump loads of small rocks are a history lesson in farming. At one time a farmer tried to convince us that it would be better to clear these for a straight run from our dairy barn back to the bush – it for sure were words heard in heaven by the McDonnell family ancestors who built this farm from scratch– a shudder, a gasp at the thought that in moments the work that had taken decades of teams of men and oxen to place safely outside planted fields would be demolished. Don’t worry our Celtic sensibilities and love of history held firm the peaks of these rocks running the frames of our fields. While we will not get rich growing our hay and market garden vegetables and fruits, we are proud to be participating in a renewal of interest in the farming era of our ancestors. Our commitment as a farming family to our community is rooted in my McLeod ancestry as possibly as a good friend of ours says, “Maybe we’re distant cousins?!”

Galvanizing as a regional farming community becomes paramount for survival against all corporate chatter – as those farm REITs pushing large investor interests are coming and divided we fall. To take a cue from another movie featuring the Celtic connection to the land is to paraphrase the quote by Mr. O’Hara in “Gone with the Wind” when he grabs a handful of soil and says, “Katie Scarlett you will always have Tara.” Let’s make sure that our children and their childrens children have our fields, and not let the anonymous investor who doesn’t know a turnip from a beet have the key to our very existence.