By Jakob Vogel B.Sc (Agr.)

AgriNews Contributor

With the spring that came in like a lion, our first demonstration of heat stress happened a few weeks earlier than normal.

Although not long lived, the reality hit again that many facilities are not ready for the summer heat.

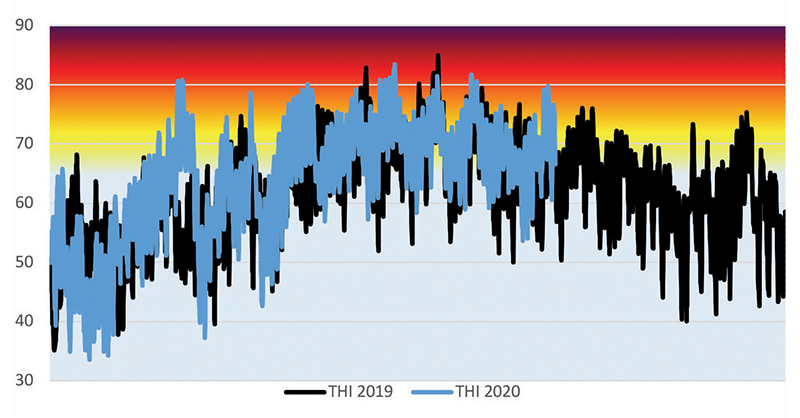

As seen in figure 1 the impact of heat stress is measured using a scale combining both temperature and humidity, because as we know – the combination of these two metrics can significantly amplify the stress suffered by the cow. Although every year is different, the tracking of the temperature humidy index (THI) can be easily done using weather station data. Now, with that in mind, it is important that the weather station data does present a certain level of bias since this data does not include the effect coming from the cows within the barn. To accurately determine the THI and the degree of heat stress on your farm, it is important to measure both the temperature and humidity in your facility.

When considering heat stress, we tend to primarily assess the lactating group of cows, which makes a lot of sense – who’s making milk right now? Where can I invest for the biggest bang for my buck?

Unfortunately, we have a tendency of forgetting a very crucial part of the dairy – dry cows! These ladies, although they may not be producing at the moment, they are the soon to be milk producers and need additional care and comfort to ensure their next lactation is as successful as possible. The dry period of a dairy cow is comparable to a well-deserved vacation when she will recover and grow in all the right ways.

During the dry period, there is significant cellular regeneration within both the rumen and udder tissues which will lead to both healthier and more productive cows. Although the ideal length of the dry period may be debated among members of the dairy industry, the fact remains, cows need a dry period and during that period we need to ensure that their comfort is not compromised.

In addition to added space and investing in bedded pack areas for the dry cows, heat abatement strategies need to be made for them as well. When analyzing herd DHI or production data, it can be noticed that there is a significant decrease in production within the fall months. Some of this may be in relation to transitioning into need feeds which may be unfermented. However, there is substantial evidence provided by the University of Florida which would support the two month “lag” directly impacted by heat stress.

In addition to the direct impact heat stress will have on the cow during her dry period, there is also the impact heat stress will have on the calving. With an increased risk of dystocia, also comes an increased likelihood of retained placenta, metritis and other related metabolic calving disorders. The impacts that are discussed a little less are the direct implications on the calf.

We need to also consider the impacts on the calf in utero and the impacts a hard calving can have on this future lactating cow. Although the actual figure is debatable, the impact on the calf in utero has been estimated to be in and around the 500 kg of production on her first lactation. This is a substantial implication considering the environmental impacts are making their mark prior to her being born.

The take home message here is to make sure we do not compromise ventilation and heat abatement on our dry cows. Active cooling of cows has been shown again and again to produce better and easier calvings, better lactations and most importantly improved heifer productivity in their first lactation.

The use of fans, shade should be the fundamental start point for heat abatement in our dry cows. Sprinklers can also be incorporated into a dry cow pen just as easily as a lactating group.