Blue planet

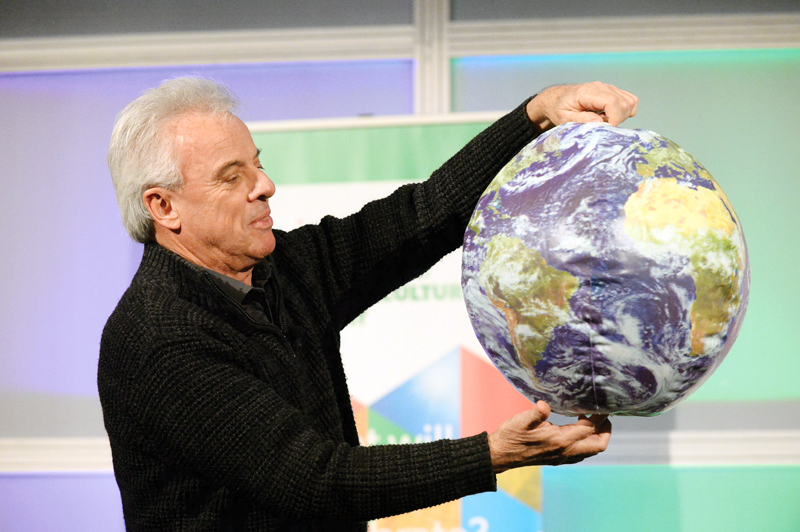

Bob MacDonald, host of CBC Radio’s Quirks and Quarks and a bestselling author, gave attendees at the Canada’s Agriculture Day conference in Ottawa a big-picture view of our planet, and the thin film of air and water covering it. Courtesy photo

by Candice Vetter

AgriNews Staff Writer

OTTAWA – Bob MacDonald, host of CBC Radio’s Quirks and Quarks and a bestselling author, was the final speaker at the Canada’s Agriculture Day conference at the Westin Hotel in Ottawa on Tues., Feb. 13.

MacDonald is brilliant at making complex scientific issues understandable and meaningful, and he does it in a fun way. His efforts in promoting science have earned him recognition at the highest level. He is an Officer of the Order of Canada and has received the Queen’s Jubilee Medal.

He pleased his audience when he started by praising the agriculture industry’s use of science and innovation to feed the seven-billion+ human population. “I’m here as a consumer. Thanks for the food!”

He also got a laugh with a story showing the differences in styles of food production in Canada. An Alberta rancher told a Nova Scotia fisher it would take from sun up to sundown to drive around all his land, to which the Nova Scotian replied, “Yeah, I had a truck like that.”

Starting far out in the solar system, MacDonald described other places we can find ice. Both Europa (the fourth-largest moon of Jupiter) and Enceladus (the sixth-largest moon of Saturn) have ice crusts with deep liquid oceans beneath the crust. Scientists are considering the possibility that under these seas there could be life which uses chemosynthesis, much like near the hot vents deep in our own ocean.

Water appears as ice elsewhere in the solar system too. On Pluto water ice is as hard as steel, due to its extremely cold temperatures. There are also nitrogen and methane ices on Pluto. Nitrogen forms glaciers, but those glaciers move much more quickly than water ice glaciers do. And there are ice mountains as high as the Rockies, but there may still be liquid water inside Pluto.

Then he moved out farther, discussing the over 3,000 exoplanets (planets found around stars other than our sun), and one of the most exciting exoplanet discoveries, the Trappist 7 system. Trappist 7 has seven planets which are in the Goldilocks, or habitable, zone from its star. However, the star is a red dwarf which is much cooler than the sun, meaning the planets are very close. That closeness means they are probably gravitationally locked the way the moon is locked to the Earth, resulting in one fried side of the planet and one endlessly cold and dark side. Is there a small habitable area on planets where the two sides meet? We don’t know. “So there are lots of planets out there,” said MacDonald, “but not another Earth. And if there are other Earths, they are very, very far away. We can’t be there.” He pointed out that the last time a human had taken a photo while far enough away from Earth to fit the whole planet in the image was 1972, from Apollo 17.

MacDonald’s talk then moved inward, revolving around the small blue planet we call home. Using an inflatable beach ball “Earth” he illustrated how thin the atmosphere is. “If the Earth was the diameter of half an apple, the apple’s skin would be the equivalent of our atmosphere,“ he said. “Our atmosphere is so thin we can walk out of it. We can do that in the Himalayas, we can walk right out of our atmosphere.”

He also showed how much water there would be at the scale of the beach ball. A pitcher of water represented all the water on Earth. Of that the vast majority (90 per cent) is salt water and undrinkable. Of the remaining fresh water, 90 per cent is locked up in ice. Of the 10 per cent left, much is deep in the ground, is stored in plants, and is floating in the atmosphere. Of what remains there is other water that isn’t potable for some reason, and the remaining drop in the pitcher represented all the potable water available – which was not very much, a mere .03 per cent of all the water on Earth.

But of that tiny amount remaining, 20 per cent is found in Canada. “We are the waterkeepers of the world,” he said.

He also said only about 30 per cent of the land on the planet is above sea level, and of that much is desert, is in the Arctic or Antarctic, or is not arable. Only 15 per cent of all the land on the planet can be farmed. Of course, much of that is already covered with cities, houses and industry, and we cannot use every bit of arable land for food production, but must leave natural spaces too. “Unfortunately, agricultural land is perfect urban land,” he said.

So that is the conundrum, continuing to grow food when we have no extra land or water left to grow it with. He recognized the attendees at the conference for their uses of science and innovation to. “You’re using science!” Technology shows in machines, chemistry shows in fertilizers, biology is evident in engineering foods and breeding, and hydrology is the science of water. “All these sciences are involved,” he said. “So when you face science detractors, you can’t say, oh, they’re just crazy. You have to face them. If you do meet opposition you must face them.”

He closed by reminding the audience, “This land you’re working on is rare. What you have is an absolute treasure in your hands.”