Courtesy Photo

By Jakob Vogel, Agr.

AgriNews Contributor

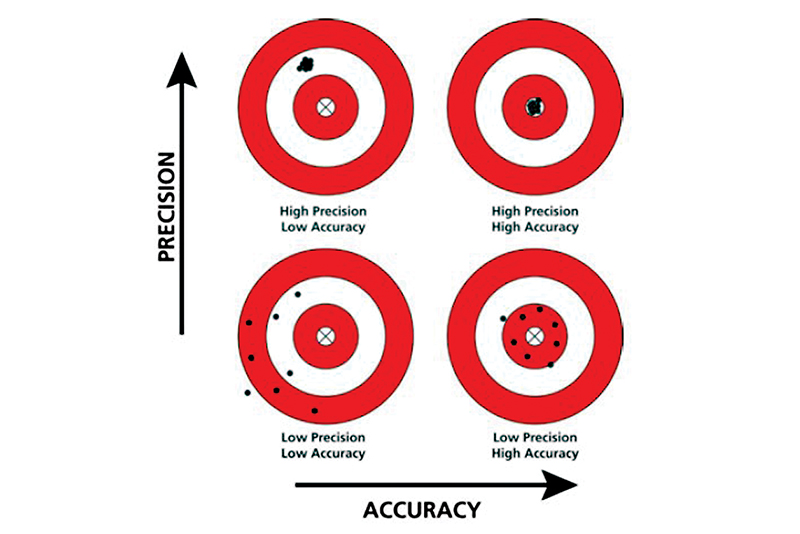

It is important to appreciate the subtle differences between precision and accuracy. Both of these tools are being adopted more frequently with practical approaches, and while accuracy is the ability to approach a specified target, precision is the ability to replicate results repeatedly regardless of their alignment with the target.

Producers that are equipped with precision ag technologies will notice that recalibration of finger meters is super important to ensure accuracy of these tools, ultimately increasing the ROI by essentially reducing the wastes (skips, or doubles) within the rows being planted in the field.

Although the term “precision agriculture” is tossed around readily by most agronomists and crop consultants (including machinery dealerships), it is interesting that this term has never made it into the barn, where, for a significant number of livestock producers, there is significant money left on the table due to a simple lack of calibration!

When considering the various areas of the farm business that rely on technology, the list (as time goes on) gets longer and longer, what with the increasing number of milking robots, automated feeding systems and certainly activity monitors for assisted breeding. With this increased uptake of automation however, comes the need to recalibrate the equipment to ensure that we are not over or under estimating their efficacy, in other words, to ensure that our “precise” (consistent) readings are also still “accurate” (aligned with target) readings.

Calibration can be done in various ways, and most of the time there are members of your farm management team that are available to assist you with the re-aligning of your technologies. For the sake of space, we will focus on the calibration of livestock diets and how increased precision and accuracy can easily be achieved at the farm along with interesting economic returns.

The baseline must consist of knowing an accurate dry matter intake of the herd. Once the accurate dry matter intake is measured, the rest is simply incorporating frequent dry matter testing of on farm forages. For example, we may consider an average farm with a dry matter consumption of 25.0 kg. It is very normal for moisture content of forages to change on farm, whether due to changes in cuts, changes in fields or simply the time of day at which the silage was harvested. For the majority of producers, this change in moisture leads to one of two things: typically, an increasing batch size (cow numbers) which typically precedes a quick call to the nutritionist. These “calibrations” take at most one hour per ingredient being used.

Economically speaking, as forages get wetter and the producer decides to increase cow numbers, we need to remember that not only forages are being increased but also purchased supplements, grains and minerals. For the above example of 25 kg of average intake and the producer needing to increase the batch by 6 per cent, this increase is followed through all of the ingredients within the diet. So as we break down the diet and assume 3 kg of supplement, 7 kg of grain corn and 200 g of a fat supplement, this could lead to 180 g, 240 g and 12 g of supplemental supplement, corn and fat, respectively. Although these increases may seem negligible, the economic value can quickly interfere with baseline profit margins!

It is important that the evaluation reflect the variation in the costs of ingredients, based on region and supply. Assuming an average supplement at $900 per tonne, grain corn (ground) having a market value of $330 per tonne and fat valued roughly at $2,500 per tonne, this seemingly harmless increase of batch size yields an additional cost of $0.27/cow/day!

If we assume a 100 cow dairy in the above example, that does not yet have the correct equipment, the investment would be paid off in just over 2 weeks considering the dilution (a batch increase of even just 6% can take time to realize and often happens over a few weeks). Additionally, if we add the cost of time requirements (2 hours per week at a rate of $20 per hour), investment extrapolated throughout the year (52 weeks) will be paid off in the initial 11 weeks of the year, thus leading to improved profits for the remaining 41 weeks of the year.