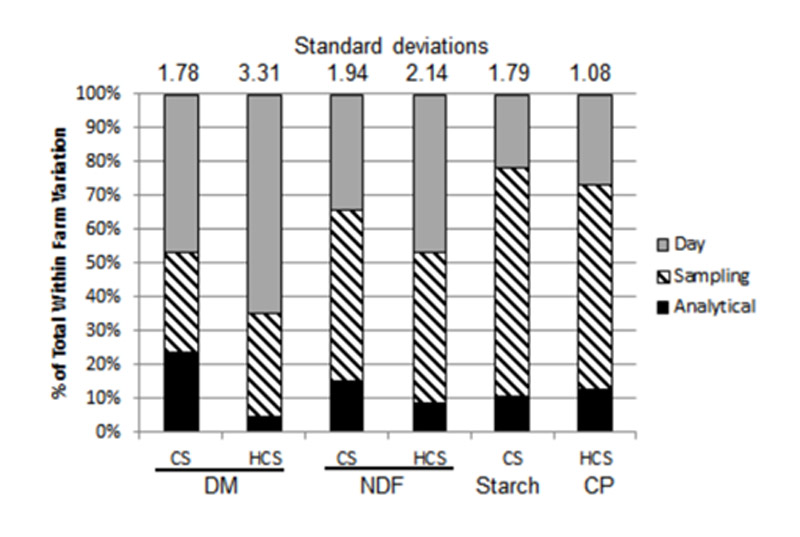

Figure 1: on farm variation over 14 day period. Adapted from W. Weiss 2016

By Jakob Vogel agr.

AgriNews Contributor

Samples are taken frequently at the farm. Whether they be soil samples, milk samples or feed samples, all consultants on the farm rely on these results to make their subsequent recommendations that are all geared toward reaching your (producer) goals.

With the taking of samples being almost part of the ‘routine’ for many operations, it may be interesting in taking a step back to ask yourselves why that sample was just taken.

Or in a more precise case; what will this set of samples bring me as a business owner?

If we start off with milk samples, these may be taken for a couple of different reasons, but all focused on milk quality.

Whether these samples are taken for mastitis identification or overall composition (monthly milk testing), the decision to voluntarily cull a cow based on her performance or milk quality status should not be taken lightly.

As we know, there is opportunity in both the value of milk, and the overall performance of the herd when linear score is found to be over 4. With that, it would be a shame to ship the highest producing cow from the herd because she comes back positive with possible mastitis.

Now for some producers, the reaction is immediately to ship this animal as she has not become a detriment to the success of the overall herd, while other producers would re-test to ensure that the analysis was correctly done in order to limit the negative repercussions.

Now that being said, if you are confident with the testing method, this second round of testing may not be required or even useful to you as a producer.

The same goes for soil sampling and feed sampling.

When feeds are sampled correctly, not only can we be more confident with the recommendations coming from the nutritionist, but we are also able to have a better control of the variation that can come through small manageable changes over time. When starting this discussion, we can easily compare the diet to a house being built.

When we start considering the forage samples to the foundation of the ration (house), we need to make sure they are secure and solid (well taken and representative) before adding more things to it (in the case of the diet these would include minerals, supplements, grains and other additives).

Depending on the storage style of the farm, the exact procedure may be altered, however it is important to remember that the ideal forage sample needs to be as representative as possible especially since most sample bags hold roughly 300 – 400 g of sample.

In a recent presentation from the Weiss research group out of Ohio State University, the origin of fluctuations within the diet were isolated and measured.

Interestingly enough, the common sense aspect of sampling was brought to the forefront and re-enforced.

As seen in Figure 1, the 3 main sources of variation come down to differences from the day of sampling (moisture content – to be discussed shortly), the analysis of the sample once ended at the lab, however the most important source of variation was the sampling technique itself.

Knowing most of the variation comes from the sampling technique itself, stemmed the development and validation of subsequent sampling techniques that are used throughout the industry.

Going as precisely as observing if the hand of the sampler was facing up or down during the sampling, it is important to ensure that these samples are being taken the proper way based on the type of forage being sampled.

For example, it is imperative during the sampling of corn silage that the hand of the sampler be facing up to ensure that limited amounts of small particles are dropped on the ground, thus adding bias to the sample.

Once the sample is sent to the lab and the analysis has been received, the remaining variation can be managed by validating the dry matter of the forages.

In the most common example that we observe on farm being to simply increase the number of cows being fed (example herd has 50 cows but producer is batching for 55), it is important to understand the increased feed cost associated with this decision rather than updating/validating the dry matter of the forages. For a simple diet consisting of 6 kgs of dry corn and 3 kgs of supplement, the additional cost of purchased feeds can easily top 10 cents per cow per day, and total costs well over 40 cents per cow (considering both corn silage and haylage in the diet).

All these additional costs for the exact same milk production!